Asylum seekers stuck in Indonesia limbo

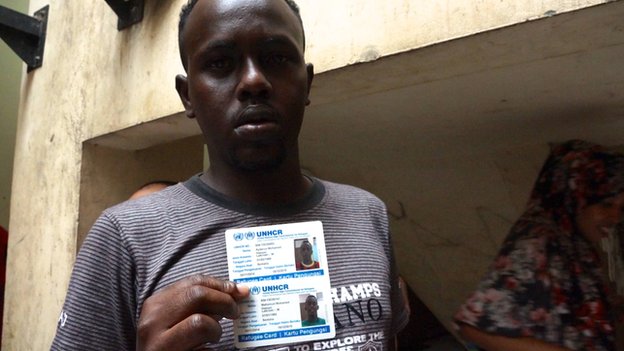

Ahmed, 30, lost his father and brother to fighting in Somalia. “Life is not possible in Somalia,” he said.

That’s why he made the decision to travel 11,000 km (6,835 miles) in search of a better life.

When he met someone who promised to take him to Australia, he agreed to pay the man $4,000 (£2,567) and flew from Ethiopia to Malaysia.

He stayed for a few days in the Malaysian capital, Kuala Lumpur. One evening around midnight, he and two other Somali men were taken to a boat that he thought would take them to Australia.

But when they reached shore, they were abandoned by the man they had paid and found out that they were in Indonesia.

Ahmed’s story is repeated by thousands of other men, women and children in Indonesia’s over-crowded detention centres.

There are around 10,000 asylum seekers in Indonesia, mostly from parts of Asia, the Middle East and Africa. They came because they thought they could find onwards passage to Australia.

But the Australian government does not want them. Since the middle of 2013, successive governments have adopted increasingly tough policies aimed at deterring them.

Boats carrying asylum seekers have been turned back and those who have made it are being detained in crowded offshore camps.

Even if they are found to be refugees, they will not be settled in Australia, its government said.

Last month, Australia went further. Under a new policy, it says that anyone registering as a refugee with the UN in Indonesia on or after 1 July 2014 would be ineligible for resettlement in Australia – leaving people like Ahmed in limbo.

“I didn’t hear that the Australian government didn’t accept refugees,” Ahmed said. “I heard it when I reached Indonesia. That’s why I trusted (the people smugglers). I didn’t believe that they could deceive me.”

Australia says the policy “is designed to reduce the burden, created by people smugglers, of asylum seekers entering Indonesia”.

But officials at an Indonesian immigration detention centre in Medan, about 182 nautical miles from Kuala Lumpur, said the boats kept coming despite the change in policy.

‘Over capacity’

The detention centre has a capacity of 150, but currently almost 400 people live there, including dozens of children, some as young as one.

“It is a burden for us,” said Purba Sinaga, the man in charge. “All detention centres in Indonesia are over capacity.”

He said the building was not designed for long-term accommodation, which explained the lack of basic facilities like bedrooms.

Some people bunked together in hot and dingy rooms. Others slept on the top floor, an open concrete space separated only by tarpaulins that divided the room into tiny cramped quarters shared by five or more people.

The stench of sweat and urine was overwhelming. The central part of the building, which serves as the dining room, is regularly flooded.

Detainees said fights often broke out because of ethnic tensions, personal grievances or just frustration.

Asylum seekers whose stories sound a lot more like economic migrants than genuine refugees are precisely the kind of people Australia wants to deter.

Immigration Minister Scott Morrison said the new policy was to stop people from “seeking to exploit the (UN refugee) programme by shopping for resettlement through a transit country”.

Indonesia, however, is not happy. Foreign ministry spokesman Michael Tene said Indonesia regretted the “unilateral decision by Australia”, saying it ran counter “to the spirit of co-operation and collaboration”.

The Indonesian foreign minister also summoned the Australian ambassador to express Indonesia’s strong opposition to the policy.

And the tough stance has only worked on a few people at the Medan detention centre.

Mr Sinaga said one man from Sudan and an Iraqi family of three had agreed to go back to their countries. But the majority of the detainees would rather bear the conditions in Medan than go home.

When I asked Ahmed, who arrived in Indonesia around the time Australia announced its new policy, what he wanted to do, he too was adamant that he could not go back to Somalia. But he wanted to warn the Somalis about the people smugglers.

“They will deceive you like they deceive so many others,” Ahmed said. “I’m telling you not to come to this place. There’s no way to go to Australia.”

Source: BBC