62-year-old Somali American woman from Minnesota found alive after thought to have been killed in Mecca’s fatal stampede

After the special morning prayers of Eid al-Adha last Thursday, one St. Paul group abandoned its much-anticipated festive activities during the Islamic holiday commemorating the end of the annual Islamic pilgrimage in Saudi Arabia.

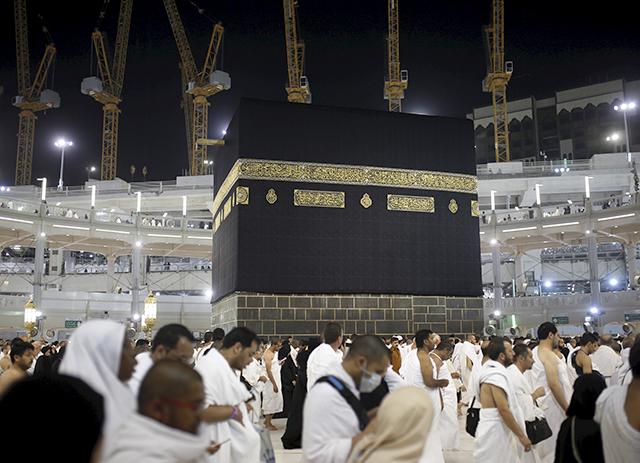

Instead, the group of family, friends and neighbors filled a small mosque in south St. Paul, praying in silence and mourning the death of 62-year-old Dahabo Farah Ebar, whom they thought was killed in a fatal stampede on the outskirts of the Muslims’ holy city of Mecca.

“She was popular in the neighborhood and was loved by everyone,” said Feisal Adan. “We canceled the Eid. The entire neighborhood gathered at her house. It was a sad moment for all of us.”

Two mosques in St. Paul also held special prayers for Ebar, who left St. Paul just two weeks ago to fulfill her Hajj duties. Congregations were told that Ebar was one of more than 700 pilgrims who lost their lives on Thursday in the stampede in Mina as they carried out a symbolic stoning of the devil, one of the final Hajj rituals.

But what happened later in the day astonished all: Ebar called her son, Farhan Sheikhdon, and told him that she had been lost in the crowd and her phone had died.

Sheikhdon then turned to the mourners, telling them that Ebar was in fact alive and well. “People didn’t believe she was alive,” he added. “They were talking to her until midnight.”

Calls went unanswered

The story of Ebar’s death surfaced after she went missing for 24 hours and several calls to her went unanswered. Then, a man in Ebar’s travel group, which was organized by Abubakar As-Siddique Islamic Center in Minneapolis, told the family that she had died.

Sheikhdon called the center to confirm if his mother was actually dead. Leaders at the center told him that nobody in the group was reported dead — but they also couldn’t confirm that she was alive, Sheikhdon said.

Anytime Sheikhdon called her cell phone, he was sent straight to voicemail — and the dozen other sources he tried weren’t able to locate his mother. Again, Sheikhdon called the man who had reported her death. “Your mom is gone,” he told Sheikhdon. “Her name was among the list of people who were announced dead.”

Sheikhdon then called several people in the Somali community to try to determine the man’s trustworthiness. “They told me that he’s a gentleman, that he doesn’t lie. That was when I accepted her death.”

Rushing to find more pilgrims

Ebar’s family and friends weren’t the only people whose loved ones disappeared into the Hajj crowd. Other Minnesotans, like Hussein Yussuf of Minneapolis, also rushed to search for their family members who had been missing without a trace for a dozen hours.

When Yussuf’s parents left their south Minneapolis home for Mecca two weeks ago, he began to pay close attention to the region. He said he wanted to be mentally prepared for any violent possibilities that could erupt in the Middle East, a territory unknown to him and to his family.

“I’ve been monitoring the news since the day my parents left,” said Yussuf, who set up a Google Alert to track the happenings in Saudi Arabia. “At about 2:30 a.m. on Thursday, I heard [a Saudi official] say that many people died in the Hajj.”

Yussuf picked up his cell phone to call his parents: “I called them more than 20 times,” he added. “No answer. I assumed the worst. Death.”

And the more he waited for the news about his parents, the more his panic grew as he learned more about the rising death toll in Mina.

On Wednesday night, Yussuf’s parents had told him they were going to Mina Thursday morning, the same time the unfortunate news unfolded with images of dead bodies wrapped in white clothes surfacing on social media. “I couldn’t sleep that night,” he said. “I wasn’t sure what to do.”

At about 7:20 a.m., Yussuf asked his uncle to try to call his parents. Fortunately, he said, they answered: “They were part of the groups that did the stoning earlier of the day,” he added. “They were not there when the incident happened.”

Growing concerns

Some Minnesotans and future pilgrims have expressed concerns about the safety during the Hajj rituals. Just two weeks before Thursday’s tragic deaths, according to news reports, 107 people died and 238 others were injured after a crane collapsed at Mecca’s Grand Mosque.

Kanwal Singh, a longtime travel consultant at the University Travel Service in Minneapolis, said the trampling death incidents in the Hajj have been common over the years. In his estimate, about 300 pilgrims die there every year.

According to officials from the Saudi Arabia government, the extreme heat and the pilgrims rushing to rituals and pushing against each other might have been factors in the stampede.

Nearly 3 million Muslims from around the world attended the Hajj, a pilgrimage prescribed to all Muslims who are financially and physically able to travel to Saudi Arabia at least once in their lifetime to perform Islamic rituals.

This year, 14,000 Muslims throughout the United States traveled to the Hajj, Singh said, with 600 people leaving from Minneapolis.

Traveling to the Hajj — the largest mass gathering in the world — is often so competitive that some people apply for visas nine months before the event, which falls in the 12th month of the Islamic lunar year. In Minneapolis, 400 applicants were turned away this year alone, Singh added.

According to a BBC news report, more than 2,800 people died in stampede tragedies during Hajj rituals between 1987-2006.

“The place is really hot and overcrowded,” said Abdirashed Elmi, a Minneapolis community organizer. “They should create a better system next year. You know, the death of 800 people is a big, big loss.”

allthingssomali.com